Randomness in blockchain protocols

We have published today a short paper that describes the randomness beacon that is used in NEAR Protocol. In this accompanying blog post we discuss why randomness is important, why it is hard, and how it is addressed in other protocols.

Many modern blockchain protocols, including NEAR, rely on a source of randomness for selecting participants that carry out certain actions in the protocol. If a malicious actor can influence such source of randomness, they can increase their chances of being selected, and possibly compromise the security of the protocol.

Distributed randomness is also a crucial building block for many distributed applications built on the blockchain. For example, a smart contract that accepts a bet from a participant, and pays out twice the amount with 49% and nothing with 51% assumes that it can get an unbiasable random number. If a malicious actor can influence or predict the random number, they can increase their chance to get the payout in the smart contract, and deplete it.

When we design a distributed randomness algorithm, we want it to have three properties:

- It needs to be unbiasable. In other words, no participant shall be able to influence in any way the outcome of the random generator.

- It needs to be unpredictable. In other words, no participant shall be able to predict what number will be generated (or reason about any properties of it) before it is generated.

- The protocol needs to tolerate some percentage of actors that go offline or try to intentionally stall the protocol.

In this article we will cover the basics of distributed random beacons, discuss why simple approaches do not work. Finally, we will cover the approaches used by DFinity, Ethereum Serenity, and NEAR and discuss their advantages and disadvantages.

RANDAO

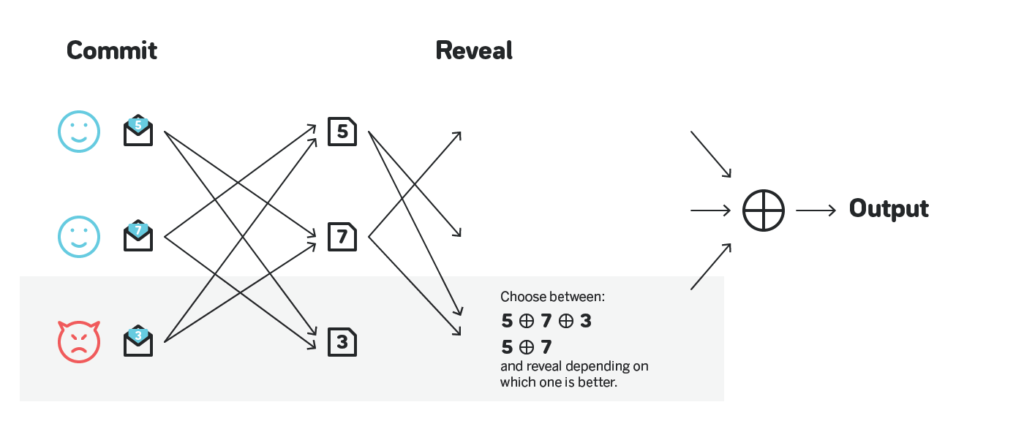

RANDAO is a very simple, and thus quite commonly used, approach to randomness. The general idea is that the participants of the network first all privately choose a pseudo-random number, submit a commitment to such privately chosen number, all agree on some set of commitments using some consensus algorithm, then all reveal their chosen numbers, reach a consensus on the revealed numbers, and have the XOR of the revealed numbers to be the output of the protocol.

It is unpredictable, and has the same liveness as the underlying consensus protocol, but is biasable. Specifically, a malicious actor can observe the network once others start to reveal their numbers, and choose to reveal or not to reveal their number based on XOR of the numbers observed so far. This allows a single malicious actor to have one bit of influence on the output, and a malicious actor controlling multiple participants have as many bits of influence as the number of participants they are controlling.

RANDAO + VDFs

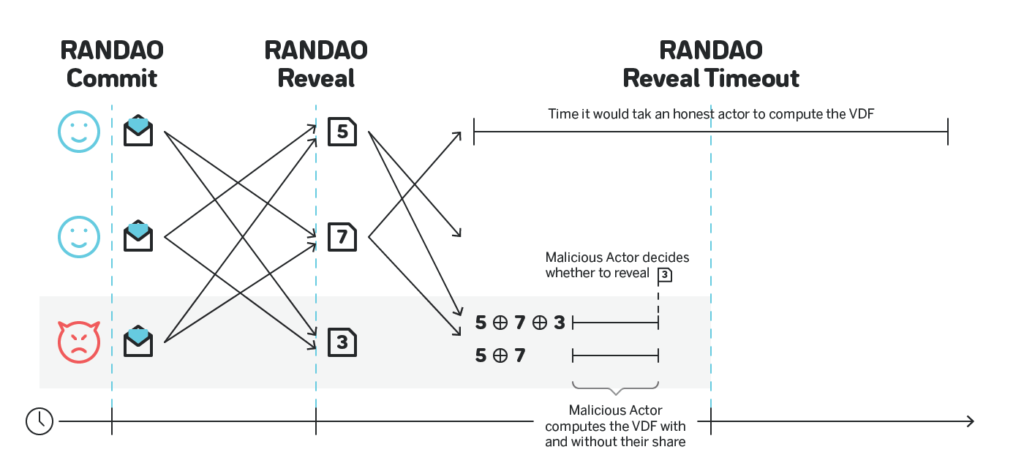

To make RANDAO unbiasable, one approach would be to make the output not just XOR, but something that takes more time to execute than the allocated time to reveal the numbers. If the computation of the final output takes longer than the reveal phase, the malicious actor cannot predict the effect of them revealing or not revealing their number, and thus cannot influence the result.

While we want the function that computes the randomness to take a long time for the participants that generate the random number, we want the users of the random number to not have to execute the same expensive function again. Thus, they need to somehow be able to quickly verify that the random number was generated properly without redoing the expensive computation.

Such a function that takes a long time to compute, is fast to verify the computation, and has a unique output for each input is called a verifiable delay function (VDF for short) and it turns out that designing one is extremely complex. There’ve been multiple breakthroughs recently, namely this one and this one that made it possible, and Ethereum presently plans to use RANDAO with VDF as their randomness beacon. Besides the fact that this approach is unpredictable and unbiasable, it has an extra advantage that is has liveness even if only two participants are online (assuming the underlying consensus protocol has liveness with so few participants).

The biggest challenge with this approach is that the VDF needs to be configured in such a way that even a participant with very expensive specialized hardware cannot compute the VDF before the reveal phase ends, and ideally have some meaningful safety margin, say 10x. The figure below shows an attack by a participant that has a specialized ASIC that allows them to run the VDF faster than the time allocated to reveal RANDAO commitments. Such a participant can still compute the final output with and without their share, and choose to reveal or not to reveal based on those outputs:

For the family of VDFs linked above a specialized ASIC can be 100+ times faster than conventional hardware. Thus, if the reveal phase lasts 10 seconds, the VDF computed on such an ASIC must take longer than 100 seconds to have 10x safety margin, and thus the same VDF computed on the conventional hardware needs to take 100 x 100 seconds = ~3 hours.

The way Ethereum Foundation plans to address it is to design its own ASICs and make them publicly available for free. Once this happens, all other protocols can take advantage of the technology, but until then the RANDAO + VDFs approach is not as viable for protocols that cannot invest in designing their own ASICs.

This website accumulates lots of articles, videos and other information on VDFs.

Threshold Signatures

Another approach to randomness, pioneered by Dfinity, is to use so-called threshold BLS signatures. (Fun fact, Dfinity employs Ben Lynn, who is the L in BLS).

BLS signatures is a construction that allows multiple parties to create a single signature on a message, which is often used to save space and bandwidth by not requiring sending around multiple signatures. A common usage for BLS signatures in blockchains is signing blocks in BFT protocols. Say 100 participants create blocks, and a block is considered final if 67 of them sign on it. They can all submit their parts of the BLS signatures, and then use some consensus algorithm to agree on 67 of them and then aggregate them into a single BLS signature. Any 67 parts can be used to create an accumulated signature, however the resulting signature will not be the same depending on what 67 signatures were aggregated.

Turns out that if the private keys that the participants use are generated in a particular fashion, then no matter what 67 (or more, but not less) signatures are aggregated, the resulting multisignature will be the same. This can be used as a source of randomness: the participants first agree on some message that they will sign (it could be an output of RANDAO, or just the hash of the last block, doesn’t really matter for as long as it is different every time and is agreed upon), and create a multisignature on it. Until 67 participants provide their parts, the output is unpredictable, but even before the first part is provided the output is already predetermined and cannot be influenced by any participant.

This approach to randomness is completely unbiasable and unpredictable, and is live for as long as 2/3 of participants are online (though can be configured for any threshold). While ⅓ offline or misbehaving participants can stall the algorithm, it takes at least ⅔ participants to cooperate to influence the output.

There’s a caveat, however. Above, I mentioned that the private keys for this scheme need to be generated in a particular fashion. The procedure for the key generation, called Distributed Key Generation, or DKG for short, is extremely complex and is an area of active research. In one of the recent talks, Dfinity presented a very complex approach which involved zk-SNARKs, a very sophisticated and not time tested cryptographic construction, as one of the steps. Generally, the research on threshold signatures and DKGs in particular is not in a state where it can be easily applied in practice.

RandShare

The NEAR approach is influenced by yet another algorithm called RandShare. RandShare is an unbiasable and unpredictable protocol that can tolerate up to ⅓ of the actors being malicious. It is relatively slow, and the paper linked also describes two ways to speed it up, called RandHound and RandHerd, but unlike RandShare itself RandHound and RandHerd are relatively complex, while we wish the protocol to be extremely simple.

The general problems with RandShare besides the large number of messages exchanged (the participants together will exchange O(n^3) messages), is the fact that while ⅓ is a meaningful threshold for liveness in practice, it is low for the ability to influence the output. There are several reasons for it:

- The benefit from influencing the output can significantly outweigh the benefit of stalling randomness.

- If a participant controls more than ⅓ of participants in RandShare and uses this to influence the output, it leaves no trace. Thus a malicious actor can do it without ever being revealed. Stalling a consensus is naturally visible.

- The situations in which someone controls ⅓ of hashpower / stake are not impossible, and given (1) and (2) above someone having such control is unlikely to attempt to stall the randomness, but can and likely will attempt to influence it.

NEAR Approach

NEAR Approach is described in a paper we recently published. It is unbiasable and unpredictable, and can tolerate up to ⅓ malicious actors for liveness, i.e. if someone controls ⅓ or more participants, they can stall the protocol.

However, unlike RandShare, it tolerates up to ⅔ malicious actors before one can influence the output. This is significantly better threshold for practical applications.

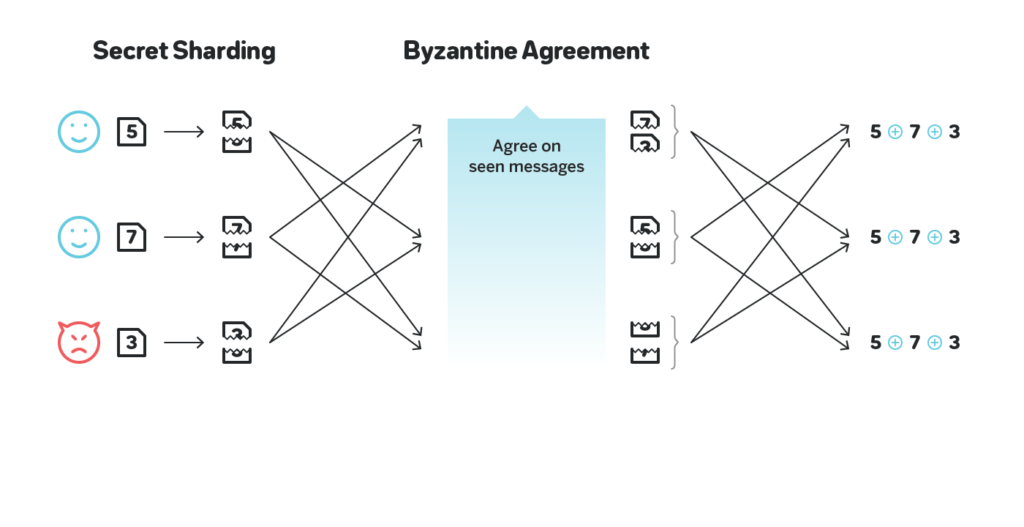

The core idea of the protocol is the following (for simplicity assuming there are exactly 100 participants):

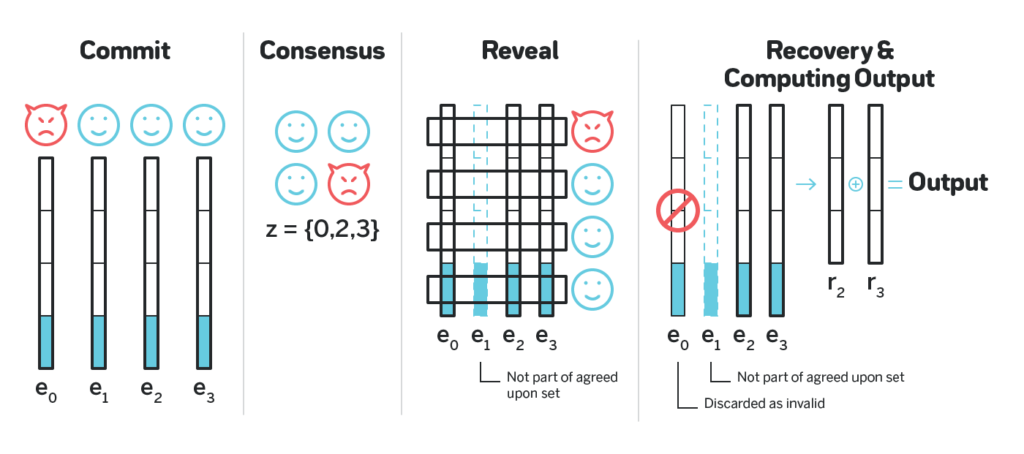

- Each participant comes up with their part of the output, splits it into 67 parts, erasure codes it to obtain 100 shares such that any 67 are enough to reconstruct the output, assigns each of the 100 shares to one of the participants and encodes it with the public key of such participant. They then share all the encoded shares.

- The participants use some consensus (e.g. Tendermint) to agree on such encoded sets from exactly 67 participants.

- Once the consensus is reached, each participant takes the encoded shares in each of the 67 sets published this way that is encoded with their public key, then decodes all such shares and publishes all such decoded shares at once.

- Once at least 67 participants did the step (3), all the agreed upon sets can be fully decoded and reconstructed, and the final number can be obtained as an XOR of the initial parts the participants came up with in (1).

The idea why this protocol is unbiasable and unpredictable is similar to that of RandShare and threshold signatures: the final output is decided once the consensus is reached, but is not known to anyone until ⅔ of the participants decrypt shares encrypted with their public key.

Handling all the corner cases and possible malicious behaviors make it slightly more complicated (for example, the participants need to handle the situation when someone in step (1) created an invalid erasure code), but overall the entire protocol is very simple, such that the entire paper that describes it with all the proofs, the corresponding cryptographic primitives and references is just 7 pages long. Make sure to check it out if you want to read a more formal description of the algorithm, or the analysis of its liveness and resistance to influence.

Similar idea that leverages erasure codes is already used in the existing infrastructure of NEAR, in which the block producers in a particular epoch create so-called chunks that contain all the transaction for a particular shard, and distribute erasure-coded versions of such chunks with merkle proofs to other block producers to ensure data availability (see section 3.4 of our sharding paper here).

Outro

This write-up is part of an ongoing effort to create high quality technical content about blockchain protocols and related topics. We also run a video series in which we talk to the founders and core developers of many protocols, we have episodes with Ethereum Serenity, Cosmos, Polkadot, Ontology, QuarkChain and many other protocols. All the episodes are conveniently assembled into a playlist here.

If you are interested to learn more about technology behind NEAR Protocol, make sure to check out the above-mentioned sharding paper. NEAR is one of the very few protocols that addresses the state validity and data availability problems in sharding, and the paper contains great overview of sharding in general and its challenges besides presenting our approach.

While scalability is a big concern for blockchains today, a bigger concern is usability. We invest a lot of effort into building the most usable blockchain. We published an overview of the challenges that the blockchain protocols face today with usability, and how they can be addressed here.

Follow us on Twitter and join our Discord chat where we discuss all the topics related to tech, economics, governance and other aspects of building a protocol.

Share this:

Join the community:

Follow NEAR:

More posts from our blog